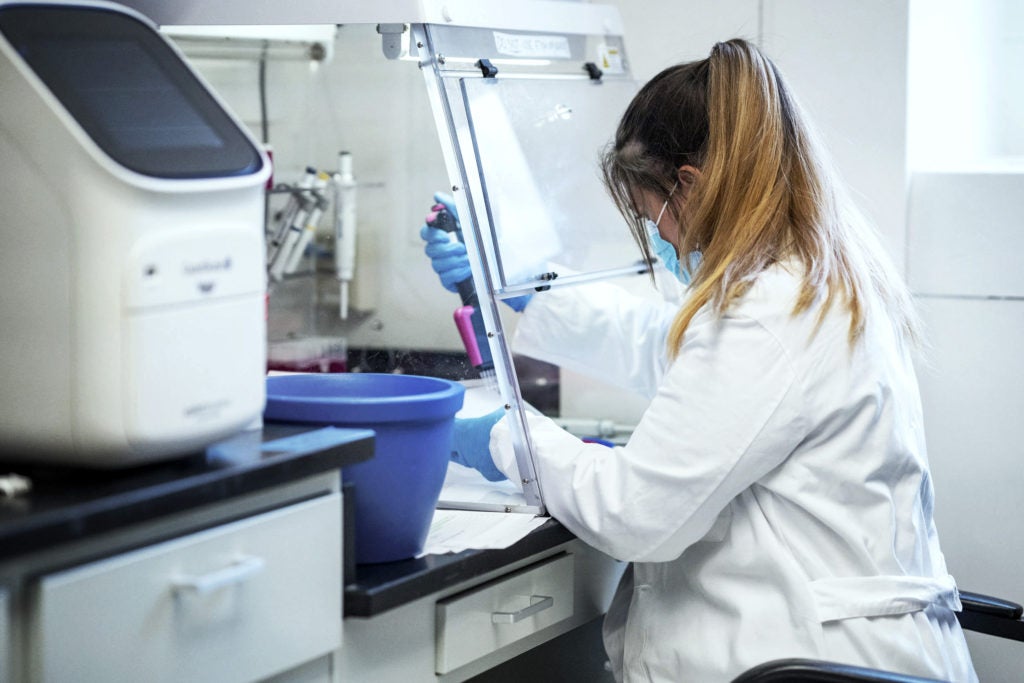

The University is analyzing wastewater drawn from collection points outside residence halls, an indicator of the presence of the virus that causes COVID-19.

Inside UVA’s Evolving Strategy to Test for COVID-19

Every afternoon this fall semester, teams at the center of the University of Virginia’s coronavirus strategy gather on Zoom videoconferences to plan the hours and days ahead.

The calls include doctors and epidemiologists; academic and operations leaders; researchers and testing coordinators. For an institution moving against an unpredictable adversary, these are forums for sharing intelligence and assessing conditions on the ground.

The strategy sessions illustrate UVA’s ever-evolving approach to confronting COVID-19 – necessary to solve a daily Rubik’s cube of emerging and shifting data, anticipation of what might happen, and decisions about how and where to take action.

There are, in fact, multiple conferences each day with different focus areas. This story draws from several consecutive days of conferences of UVA’s epidemiology team and its prevalence-testing oversight team.

The group responsible for testing oversight, among other things, reviews the number of positive cases in residence halls from each morning, looking for patterns and clues that would help them recommend a course of action. How many dorms showed new cases, and how many cases were in each location? Were the positive cases on one or multiple floors, centered on a single hallway or scattered? Were groups of roommates involved? Had the dorm been tested previously? What kinds of tests were used?

They discuss what they might learn from the latest analysis of wastewater drawn from collection points outside residence halls, an indicator of the presence of the virus that causes COVID-19. That combination of data, including the relative strength of the wastewater signal, provides useful information to help decide, for example, whether to schedule an entire dorm for virus testing.

In typical understated fashion, Mitch Rosner, MD, chair of the Department of Medicine and a constant presence across the various Zoom sessions, summed up the work at hand to his colleagues during a recent prevalence testing call.

“We’re trying to balance a lot of things,” he said after a lengthy review of the day’s situation.

At the time of another meeting in late September, several dorms – including Balz-Dobie House – had experienced concerning numbers of cases. As a result, the residents of each dorm were fully tested, with follow-up testing occurring days later, after positive students and their close contacts had been isolated or quarantined. Balz-Dobie, a dorm with more than 180 students, finished both rounds with 19 positive cases. So far in October, it has seen no new positive results – but that could change again.

Chris Holstege, MD, executive director of Student Health and Wellness, summarized the latest stats from across Grounds. On this afternoon, his review showed scattered positive cases among other residence halls, indicating the virus was showing up in more housing on Grounds, but not necessarily in concentrated numbers yet.

Amy Mathers, MD, associate professor of medicine and pathology and the leader of the wastewater analysis program, provided her latest news to the group. At the time, a handful of dorms were being monitored via wastewater testing and at least two of them were showing strong positive signals of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

With cases popping up and the wastewater pointing more strongly to specific residence halls, she and others seemed ready to recommend the next move.

“I think we have to test more dorms next week,” she said.

Evolving Programs

When UVA decided to open its residence halls for the fall semester and offer both in-person and online instruction, it required that all students who would be living or learning on-Grounds or in the Charlottesville and Albemarle County community to submit a negative COVID-19 test before moving to Grounds or beginning in-person classes.

Using a vendor called Let’s Get Checked, UVA received notice of 65 positive results from more than 18,000 pre-arrival tests submitted through early September. This represented the opening phase of UVA’s testing strategy for the fall.

As the semester began for in-person instruction, UVA’s efforts included testing those with symptoms of COVID-19, and offering voluntary, self-administered tests for asymptomatic faculty, staff and contract workers. The wastewater program soon would become a regular part of the regimen.

At the same time, UVA launched an information campaign to emphasize its expectations for wearing masks, limiting the size of gatherings and events, and other measures that contribute to preventing or minimizing the spread of COVID-19.

UVA leaders say the expanding testing and monitoring programs play a crucial, but not singular role in managing the spread of the virus. For the week ending Oct. 3, the University conducted 2,541 tests, identifying 162 positive student cases and 21 positive employee cases. On Oct. 6, UVA was reporting 200 active cases of COVID overall. Eight percent of its isolation space and 22% of its quarantine space was occupied.

“Testing is effective. It’s a tool to help the other measures work more efficiently, but you can rely too heavily on it,” Rosner said. “The bottom line is we have to work as a community that cares about one another and consistently follows the basic rules: physical distancing, wearing masks and avoiding groups or other high-risk situations. This is hard, but it is worth it.”

In September, UVA launched a random asymptomatic testing program in which a number of students each receive email notice of being selected for nasal swab tests at the Student Activities Building. Since opening for testing in late August, workers at the SAB site have conducted more than 2,500 asymptomatic tests – including random prevalence tests, and tests for those who were identified through contact tracing as being exposed to someone who tested positive.

Asymptomatic testing identifies people who have COVID-19 but otherwise feel fine, enabling UVA to isolate them and quarantine others who may have been exposed – a practice that helps contain the virus by preventing asymptomatic people from unknowingly spreading it to others.

As the programs have evolved, the University also has worked to improve logistics and address disruption that comes with moving multiple students into isolation and quarantine spaces, and assisting the Virginia Department of Health with contact tracing.

About 4,500 students live in University housing. That includes about 3,000 first-year students who already are encountering the typical stresses of leaving home to attend college and the extraordinary stresses of doing so during a pandemic.

By mid-September, UVA leaders grew more concerned as the volume of positive cases among students on-Grounds and off-Grounds trended upward. Combined with concerns about inadequate physical distancing and reports about large gatherings, UVA announced a set of tighter restrictions and signaled that even more stringent restrictions could be implemented if trends continued.

Rosner and his colleagues said the metrics they watch improved during the initial two weeks after the tighter restrictions were announced, but extending them could solidify and validate their impact and provide an opportunity to combine them with the latest evolution in UVA’s testing program: saliva rapid-screening. The tighter guidelines were extended for another two weeks on Tuesday.

A New Phase

At about the same time, the University began a new program for asymptomatic prevalence testing – saliva rapid-screening tests – and discussion among members of the strategy team reflected the potential benefits of having the additional tool.

Saliva screening allows UVA to quickly test large groups of people, with results known in a matter of hours, rather than days. During the first full week of the program, about 300 off-Grounds students were providing saliva samples per day, a number UVA hopes to significantly increase.

Of course, many more UVA students live off-Grounds than in University dorms. Those students already are among those who could be selected for random swab tests each week. As the saliva program ramps up in an initial phase directed toward residence halls, UVA will deploy its inventory of self-administered swab test kits from Lets Get Checked to off-Grounds students during the next few weeks.

More than at any time since the start of the fall academic semester, those involved in the virus-management effort appear optimistic about transitioning into a more assertive, less-reactive strategy. Bolstered by a maturing wastewater-analysis program and the emerging saliva rapid-screening program, UVA leaders see an opportunity to significantly expand testing and early-warning analysis – but they acknowledge ramping up any new program quickly will reveal unexpected obstacles that could slow progress.

“We could use the coming weeks to get into a cadence of testing every student living in a dorm every week,” Rosner suggested. “This is a practice that other schools have used with some success.”

Costi Sifri, MD, an infectious disease specialist and UVA’s director of hospital epidemiology, said the multiple testing methods and greater capacity give hope that UVA can settle into a testing rhythm that includes such repeat testing across its residence halls. Evidence from other universities shows that the approach identifies a relatively high number of positive cases in initial rounds, he said. But as asymptomatic students are more quickly identified and isolated, a university is able to reduce the likelihood of spread over time, and later rounds of testing often yield many fewer cases.

With six weeks to go before the semester’s in-person classes conclude, that would be a welcome next evolution in UVA’s virus-testing experience.

“We’ve learned a lot, and I know we have a lot more to learn,” Rosner said. “We are getting better at this, but we always know that tomorrow could – and probably will – bring us a new set of challenges. So we will take those on as they come and keep trying our best to make this as safe as it can be for everyone.”

Latest News